Get Healthy!

Staying informed is also a great way to stay healthy. Keep up-to-date with all the latest health news here.

09 Mar

Recreational Drugs Linked to Higher Stroke Risk, Major Study Finds

A new study involving more than 100 million people found recreational drugs like marijuana, cocaine and amphetamines significantly raise the risk of stroke – even in younger users.

06 Mar

Chronic Back Pain Can Make Everyday Sounds Hard to Tolerate

A new study finds patients with chronic back pain experience ordinary noise as more intense and unpleasant.

06 Mar

How Allergy Season Affects Students’ Academic Performance

In a new study, high schoolers exposed to high pollen counts during exam season scored lower, especially in math and science.

'Fibermaxxing' Trend Encourages People To Eat More Fiber

A growing nutrition trend called “fibermaxxing” is encouraging people to eat enough fiber each day, and scientists say the attention may be a good thing.

Fiber plays an important role in digestion and has been linked to lower risks of several health problems, including certain cancers. Researchers say increasing fiber intake ca...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 9, 2026

- |

- Full Page

That Stressful Person in Your Life Might Be Aging You Faster, Study Finds

Spending time with someone who constantly causes problems may do more than just ruin your mood.

Over time, those stressful relationships could also affect your health and even speed up aging, a recent study suggests.

Researchers looked at the effects of people they call "hasslers," folks who “create problems or make life ...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 9, 2026

- |

- Full Page

FDA Vaccine Chief Dr. Vinay Prasad Exiting Role

Dr. Vinay Prasad, who leads the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) division that oversees vaccines and complex medical treatments, is leaving the agency at the end of April.

Prasad took on the job last May but faced criticism during his short stint.

FDA Commissioner Dr. Marty Makary said Prasad will return to the University of C...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 9, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Infant Bath Seats Sold on Amazon Recalled Due To Tipping Hazard

Parents are being asked to stop using certain baby bath seats after officials said the products could tip over and put infants at risk for drowning.

Nearly 2,400 Trankerloop baby bath seats are being recalled because they do not meet the standard safety rules for infant bath seats, according to a recall notice from the U.S. Consumer Produc...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 9, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Many Seniors Gain Physical, Mental Fitness As They Age, Study Finds

People think of aging as a steady decline, with seniors gradually losing their physical abilities and mental agility as the years wear on.

But a new study suggests that seniors can – and often do – improve over time, with the right mindset.

Nearly half of seniors 65 and older showed measurable improvement in their brain h...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 9, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Common Drug Class Shows Links to Heart Risk -- Are You Taking One?

A common class of drugs called anticholinergics might boost risks for heart failure and other dangerous cardiac conditions, a new study says.

People taking the largest amounts of anticholinergic drugs had a 71% higher risk of heart health problems than those who didn’t use these drugs at all, researchers recently reported in the jour...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 9, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Weighted Vests Help Keep Bones Strong — But Only If Seniors Stay Active

Weighted vests – the latest internet-driven workout craze – can help older folks improve their bone health while losing weight, a new study says.

There's one caveat though: The vest won’t help your bones if you don't stay active, researchers recently noted in the journal Frontiers in Aging.

“If we're ...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 9, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Illicit Drugs Raise Stroke Risk, Even for Younger Adults

Smoking weed, taking a hit of cocaine or popping some amphetamines can raise a person’s risk of stroke – even if they’re a younger adult.

Coke and amphetamines can double or triple the risk of stroke for any adult, researchers reported in the International Journal of Stroke.

Weed also increases stroke risk,...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 9, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Small Drop In Measles Vaccinations Tied to Big Jump In Cases

Even a slight decrease in measles vaccinations could spark a seven-fold increase in new cases, a new report says.

Just a 1% annual drop in the rate of MMR (measles/mumps/rubella) childhood jabs could prompt 17,000 measles cases, 4,000 hospitalizations and 36 preventable deaths each year, concludes a new report from the Common Health Coalit...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 9, 2026

- |

- Full Page

UV Air Filters Cut Airborne Asthma Triggers, Study Finds

Ultraviolet air filters might help rid a person’s home of asthma triggers, a new study suggests.

Installing one type of UV air filter in heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems led to a more than twofold decrease in microbes linked to asthma, researchers reported recently at the annual meeting of the American Academy of All...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 9, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Most Americans Say They Don’t Trust Driverless Cars — Here’s Why

Many Americans remain uneasy about driverless cars. According to new research, their concerns go far beyond safety.

A new study from the University of California San Diego found that most Americans worry the technology could lead to job losses, with many saying it could worsen income inequality.

Waymo "robotaxis" are already in servi...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 8, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Can The Critters in Your Mouth Cause or Cure Disease?

SATURDAY, March 7, 2026 (HealthDay News) — No matter how much you brush, floss and rinse, there’s a zoo colonizing your teeth, gums and tongue.

Billions of microscopic critters called microbes make their home in your mouth, and scientists studying them suspect they play important roles in not only diseases of the mouth but...

- Carole Tanzer Miller HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 7, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Some Patients Keep Weight off With Fewer GLP-1 Injections, Study Finds

Some patients taking popular GLP-1 weight loss drugs may be able to keep the weight off while taking injections less often, according to a small new study.

The idea began when Dr. Mitch Biermann, an obesity and internal medicine specialist at Scripps Clinic in San Diego, started noticing a pattern among his patients.

Several told him...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Sixth Measles Case Confirmed in New Mexico Jail

Health officials in New Mexico say the state now has six confirmed measles cases, including a newly reported case linked to a jail in Las Cruces.

The latest case involves a federal detainee at the Doña Ana County Detention Center, according to the New Mexico Department of Health.

Officials say people who visited the U.S. Distr...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

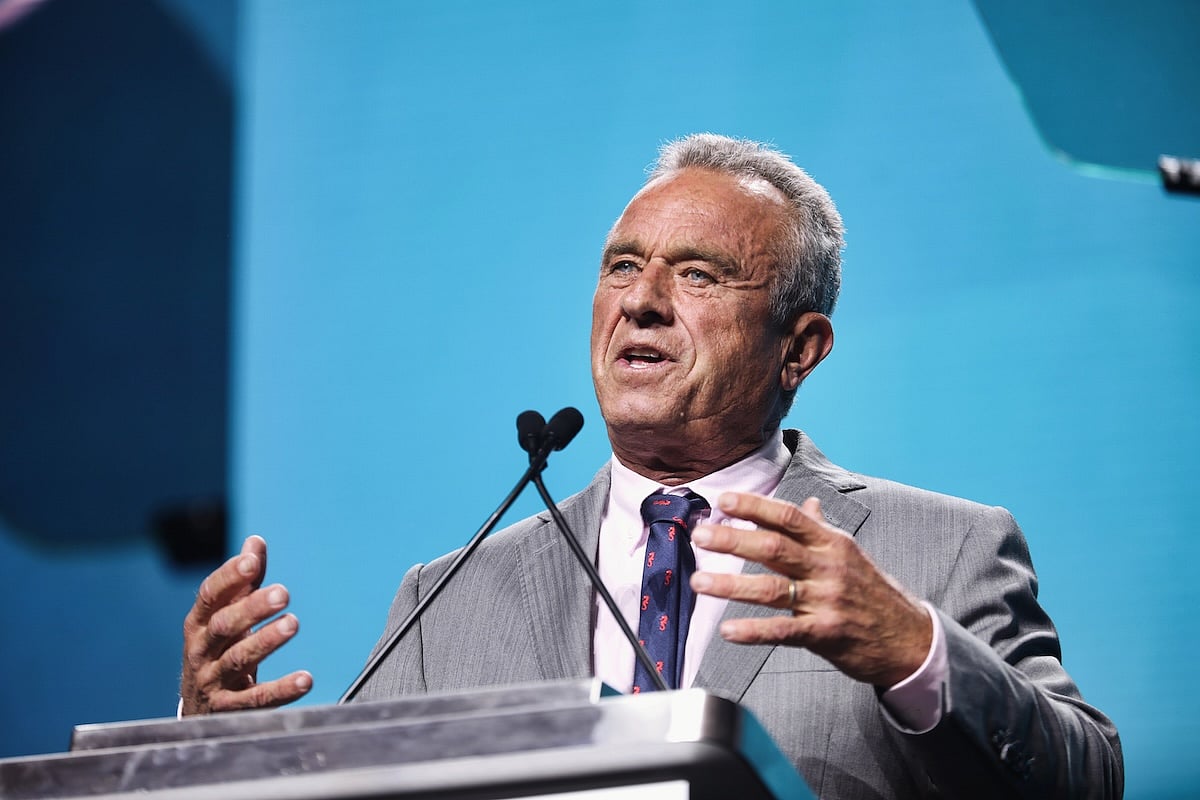

RFK Jr. Urges Medical Schools To Add More Nutrition Training

U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announced a new effort Thursday aimed at getting medical schools to spend more time teaching students about nutrition.

Federal officials say 53 medical schools have already agreed to take part in the voluntary initiative.

The program has asked schools to review their current nutrition train...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

45,000 Halo Magic Sleepsuits For Babies Recalled Over Choking Risk

About 45,000 HALO Magic Sleepsuits for infants are being recalled after reports that part of the zipper can come loose and create a choking hazard.

The recall was announced March 5 by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission and affects certain sleepsuits sold in the United States, according to safety officials.

The problem involv...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Racial Disparities Persist In Lung Cancer Treatment, Study Finds

Black lung cancer patients are less likely to receive surgery or radiation therapy aimed at curing their cancer compared to white patients, a new study says.

This gap has persisted with minimal improvement since the early 1990s, researchers reported March 2 in JAMA Network Open.

“The past 30 years have seen tremendous ...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

GLP-1 Weight-Loss Drugs Prove Effective Across Diverse Patient Groups

As the popularity of medications like Ozempic and Trulicity for losing weight continues to soar, folks may wonder: "Will they work for me?"

Researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health sought to shed light on that question by analyzing results of dozens of studies on the drugs.

The takeaway: GLP-1 receptor ago...

- Deanna Neff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Chronic Pain Can Make Noise Unbearable By Rewiring The Brain, Study Says

Everyday sounds add to the torment of a person with chronic back pain, apparently because pain rewires how the brain responds to noise, a new study says.

People suffering from back pain process sounds differently and more intensely, adding to their agony, researchers recently reported in the Annals of Neurology.

“Our f...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Angry Teens May Age Faster, Study Finds

Your confrontational, angry teenager could wind up growing old before their time, a new study says.

Aggressive behavior as a teenager is linked to faster biological aging by age 30, researchers reported March 5 in the journal Health Psychology.

These angry teens also are more likely to pack on excess weight by that age, rese...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 6, 2026

- |

- Full Page

.jpeg?w=1920&h=1080&mode=crop&crop=focalpoint)