Get Healthy!

- Dennis Thompson

- Posted June 26, 2023

Tori Bowie's Death Highlights Race Gap in Maternal Death Rates

Having a baby in the United States continues to be a risky proposition, particularly for Black women, according to a pair of new reports.

The number of U.S. deliveries that resulted in severe, potentially life-threatening complications for the mother increased between 2008 and 2021, according to a new analysis led by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).

Further, the overall U.S. maternal death rate nearly doubled during the COVID-19 pandemic, a new Commonwealth Fund report says.

Both reports found Black women to be at significantly higher risk of death or severe complications during pregnancy, delivery and postpartum compared to white women.

"The bottom line is that in the U.S. we have a pretty fractured health care system around maternal and women's health. And ultimately, any failed system affects those that are most vulnerable and most marginalized, right?"said Dr. Laurie Zephyrin, senior vice president of advancing health equity at the Commonwealth Fund.

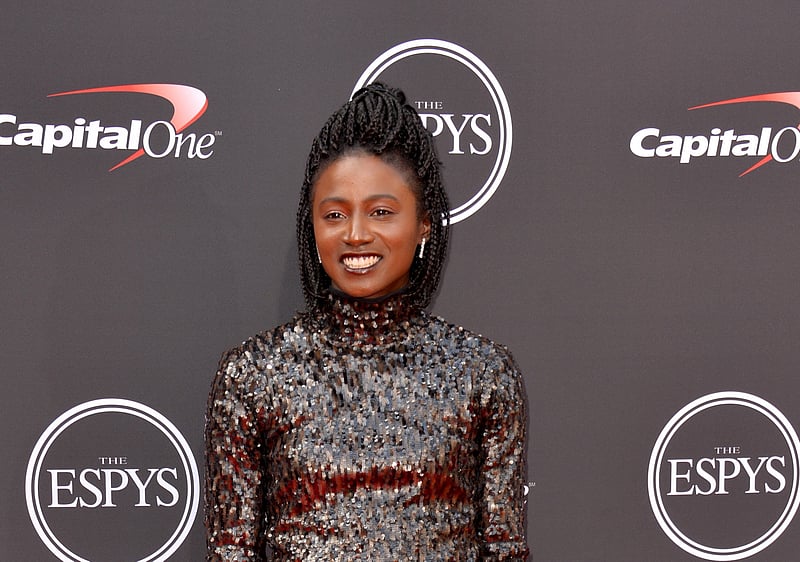

These new reports were released this week in the wake of the death of U.S. Olympic track and field star Tori Bowie, who died in May of pregnancy complications.

Bowie, 32, was eight months pregnant when she was found dead in a Florida home. An autopsy found that she appeared to be showing signs of labor when she died, and the report cited eclampsia and respiratory stress as possible complications.

Bowie's case highlights racial health disparities that increase a Black woman's risk during pregnancy, even if she's fit and financially well-off, experts say.

"Maternal mortality for Black women has nothing to do with health or economic status,"D'Andra Willis of The Afiya Center, a Black-centered reproductive justice group, told NBC News. "You could be the richest or the poorest, Black women are still three to five times more likely to die in childbirth than any poor white woman."

Dr. Angela Bianco, director of maternal fetal medicine at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, agreed.

"When you look at Black women that have the same social and economic status as perhaps a white woman, they still have worse outcomes,"Bianco said. "Even in the absence of comorbidities, they have worse outcomes. So they're not hypertensive, they're not obese, they're not impoverished, and yet they still have worse outcomes."

Maternal deaths 'nearly doubled'

The overall U.S. maternal death rate rose to 32.9 per 100,000 in 2021, almost twice the 2018 rate of 17.4 deaths per 100,000, according to figures released by the Commonwealth Fund.

These are deaths that occur during pregnancy or delivery, or even during the postpartum period.

"The U.S. maternal [death] rate nearly doubled between 2018 and 2021,"Zephyrin said. "It's actually increased dramatically among all women across race and ethnicity."

Deaths among Black and American Indian/Alaska Native women have largely driven the overall increase, the report found.

In 2021, at the height of the pandemic, the maternal death rate for Black women rose to 69.9 deaths per 100,000 live births, according to the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics.

The maternal death rate for Black women now is more than twice that of the general population, and two and a half times the rate for white women (26.6).

The death rate among American Indian/Alaska Native women is even more shocking: 118.7 deaths per 100,000 live births.

Experts note that all U.S. women fare poorly in pregnancy compared to those living in other developed countries.

"What's even more sobering is that when we look at ourselves compared to other industrialized nations -- European nations, places with national health care, New Zealand, Britain -- we are just failing,"Bianco said. "Our maternal [death] rate is just continuing to go up and theirs are flat, relative to ours. And we're supposed to have even better resources than them."

In 2020, the overall U.S. maternal death rate was 23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births -- far higher than those of Canada (8.4 deaths); France (7.6); Switzerland (7); the United Kingdom (6.5); Norway (3.7); Germany (3.6), and Japan (2.7), the Commonwealth Fund says.

But Black Americans had an even higher maternal death rate that year, with 55.3 deaths per 100,000 live births.

States with the worst maternal deaths rates are largely Southern -- Mississippi (50.3 deaths per 100,000 live births); Tennessee (46.9); Louisiana (43.8); Alabama (43); Arkansas (42.7); Kentucky (37.6); New Mexico (36.2); Georgia (35.9); South Carolina (35.3), and Arizona (34.6).

The Commonwealth Fund says it's concerned these death rates will worsen in the wake of overturning of Roe v. Wade, which has had profound impacts on women's health in states that ban or severely restrict abortion.

"The data we've presented show that in many states that have imposed abortion restrictions, women had poor health outcomes even prior to the 2022 Supreme Court ruling,"the report reads. "Twelve of the 15 states that rank lowest on our measures of reproductive care and women's health have restrictive abortion laws as defined by the Guttmacher Institute."

Not all bad news

There have been some clear improvements in American pregnancy care.

For example, U.S. women are now much less likely to die during childbirth in a hospital, according to the new DHHS study.

Delivery-related hospital deaths declined by 57% between 2008 and 2021, falling from 10.6 deaths per 100,000 in 2008 to 4.6 per 100,000 in 2021, based on analysis of data representing about 25% of all U.S. hospital admissions.

"This decline in deaths during delivery hospitalization likely demonstrates the impact of national and local strategies to improve the quality of care by hospitals during delivery-related hospitalizations,"said lead researcher Dr. Dorothy Fink, director of the Office on Women's Health at DHHS.

Bianco agreed, noting that professional organizations like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have been urging "people who care for women during delivery to focus on things that are associated with the worst outcomes."

These groups have pushed "things like toolkits to address obstetrical hemorrhage and severe hypertension and sepsis,"Bianco said. "And there's been a much greater uptake of these sort of toolkits across the board, and that's why we're probably seeing this reduction."

But the same study also found that severe complications are occurring more often during hospital deliveries, despite this increased effort to counter them.

The rate of severe complications during delivery increased to 206.1 events per 10,000 discharges in 2021, compared with 135.2 per 10,000 in 2008, according to the study published June 22 in JAMA Network Open.

These complications during delivery "increased by 2% annually, with an overall increase of 22%,"Fink said.

The most common complication was severe bleeding that required a blood transfusion. Others included dangerous blood clots, hysterectomy, acute respiratory distress, kidney failure, sepsis, eclampsia, shock and heart failure or pulmonary edema, the study said.

"I think the headline is that severe maternal morbidity is not decreasing. It is increasing,"Zephyrin said. "These can have life-changing consequences on people's lives and their family's lives."

She noted that delivery-related complications also occur much more often than maternal deaths during delivery.

"[That is something that] can really be the measure of the health of our health care system,"Zephyrin said.

And as with the overall maternal death rate, Black women and women from other ethnic backgrounds are at higher risk for delivery-related complications than white women, the study found.

Black women had a 39% higher risk of complications during delivery than white women; Asian women 33% higher; Hispanic women 22% higher; Pacific Islanders 53% higher; and American Indians 41% higher.

These complications are "likely increasing due to the overall health of U.S. women giving birth, including increases in maternal age, obesity and preexisting medical conditions,"Fink said.

Placenta previa (when the placenta covers the cervix), kidney disease, severe preeclampsia, heart disease and sickle cell disease were associated with the highest odds of complications during delivery, the study found.

Insurance, bias may be factors

Why do American women have a higher risk of maternal death and complications, particularly compared to the rest of the industrialized world?

The HHS study would seem to refute the notion that it's specifically the fault of hospital care, since delivery-rated deaths are declining, Fink said.

Much of the reporting has focused on increasing maternal death rates, she noted. "As a result, this has led many people to believe that hospitals may be the main cause,"she said.

"The decreasing [death] rates within the in-patient delivery setting is statistically significant and a welcome finding for all women,"Fink added.

Instead, the problem seems to be a lack of continuing care throughout and even after pregnancy, experts said.

Insurance coverage and societal support for pregnancy care probably is a large piece of the puzzle, Zephyrin said.

"Particularly with the ending of the public health emergency, states are redetermining eligibility for millions of people just at a time where health care is becoming more unaffordable,"she said.

Many women don't have access to any insurance coverage, or have to "skimp coverage, where you're insured but you can't get your basic needs covered,"Zephyrin said, adding that coverage problems particularly affect women with lower incomes.

But as Bianco noted, even well-off Black women have a higher risk for maternal death.

"There's a lot of focus trying to tease out why this is happening,"she said. "I think it's really encouraging that people are starting to look at this, and maybe we need to continue to work on training frontline staff about their own inherent biases and how to listen to patients and be supportive and chip away at the effects of structural and systemic racism that probably are at play here."

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that "multiple factors contribute to these disparities, such as variation in quality health care, underlying chronic conditions, structural racism, and implicit bias," in its website addressing Black maternal mortality. "Social determinants of health prevent many people from racial and ethnic minority groups from having fair opportunities for economic, physical and emotional health."

Zephyrin said the United States needs to revamp its system of pregnancy care and focus more attention on women throughout their pregnancy and even after delivery.

"Do we have an adequate maternal health care workforce? How do we address bolstering that? How do we address expanding and diversifying the maternal health workforce?"she said. "And by diversifying, I mean thinking about incorporating midwives and doulas into the workforce and also ensuring cultural diversity and ethnic diversity in the maternal health workforce."

That's the right idea, Bianco said.

"It probably really requires a very boots-on-the-ground approach,"she said. "We need to really focus on doing things like hiring more patient nurse navigators that make sure that these women are linked to ongoing care."

Bianco gives the example of a woman without proper prenatal care who arrives for delivery suffering from severe preeclampsia, a complication that risks the life of both mother and child.

"We make sure that they don't have a stroke during delivery and we hand them a healthy baby and they get discharged, and then they die from a stroke several months later or a year later because they're not linked to ongoing care,"Bianco said.

Hiring more midwives and doulas to help guide women through and after pregnancy could help, particularly if they come from a variety of ethnic backgrounds, Bianco and Zephyrin agreed.

"We really need to focus our health care dollars on these sort of ancillary services,"Bianco said. "Do we hire Black doulas, so patients that are Black will identify more with another Black individual perhaps and follow up with them postnatally? We need to have these sort of resources available."

More information

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has more about Black maternal death rates.

SOURCES: Laurie Zephyrin, MD, MPH, senior vice president, advancing health equity, Commonwealth Fund, New York City; Angela Bianco, MD, director, maternal fetal medicine, Mount Sinai Health System, New York City; Dorothy Fink, MD, director, Office on Women's Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, Md.; JAMA Network Open, June 22, 2023; Commonwealth Fund, June 22, 2023