Get Healthy!

Staying informed is also a great way to stay healthy. Keep up-to-date with all the latest health news here.

13 Mar

Ultra-Processed Foods May Be Bad for Your Bones, Study Finds

Eating too many ultra-processed foods lowers bone mineral density and raises the risk of hip fracture, researchers warn.

12 Mar

Young Mom With Stage 4 Colon Cancer Finds Hope Through a New Transplant Option

Doctors at Northwestern Medicine give a young mother with advanced colon cancer that had spread to her liver a new chance at life with an innovative treatment option – a living-donor liver transplant that significantly raises odds of survival.

11 Mar

Simple Blood Test May Predict Dementia in Women Up to 25 Years Before Symptoms

New research finds women with high levels of a novel biomarker in their blood are much more likely to develop memory and thinking problems and dementia later in life.

Bad News for Multitaskers: Your Brain Can’t Really Do It

Think you’re great at multitasking? Answering texts, listening to a podcast and finishing work at the same time?

Your brain may disagree.

A new study out of Germany suggests that people can’t truly do two tasks at once, even after lots of practice. Instead, the brain quickly switches between tasks, which can still slow pe...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 13, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Study Finds 'Forever Chemicals' on California Fruits and Vegetables

Some fruits and vegetables grown in California may carry traces of pesticides known as PFAS, sometimes called “forever chemicals,” according to a new analysis.

Researchers with the Environmental Working Group (EWG) reviewed state testing data and found PFAS pesticide residues in 348 of 930 produce samples — 37% of those t...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 13, 2026

- |

- Full Page

About 3,000 Wayfair Dressers Recalled Over Child Tip-Over Risk

About 3,000 dressers sold online are being recalled because they can tip over and seriously injure a child, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) warns.

The recall affects 17 Stories Furniture 14-drawer dressers sold on Wayfair.com, according to a notice issued March 12.

Officials say the dressers are unstable if they ar...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 13, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Microsoft Unveils AI Health Tool That Can Read Medical Records

Microsoft is rolling out a new artificial intelligence (AI) tool designed to help people manage their health.

The feature, called Copilot Health, works inside the company’s Copilot app and can provide personalized health advice using a user’s medical data, if the user chooses to share it.

With permission, the tool can rev...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 13, 2026

- |

- Full Page

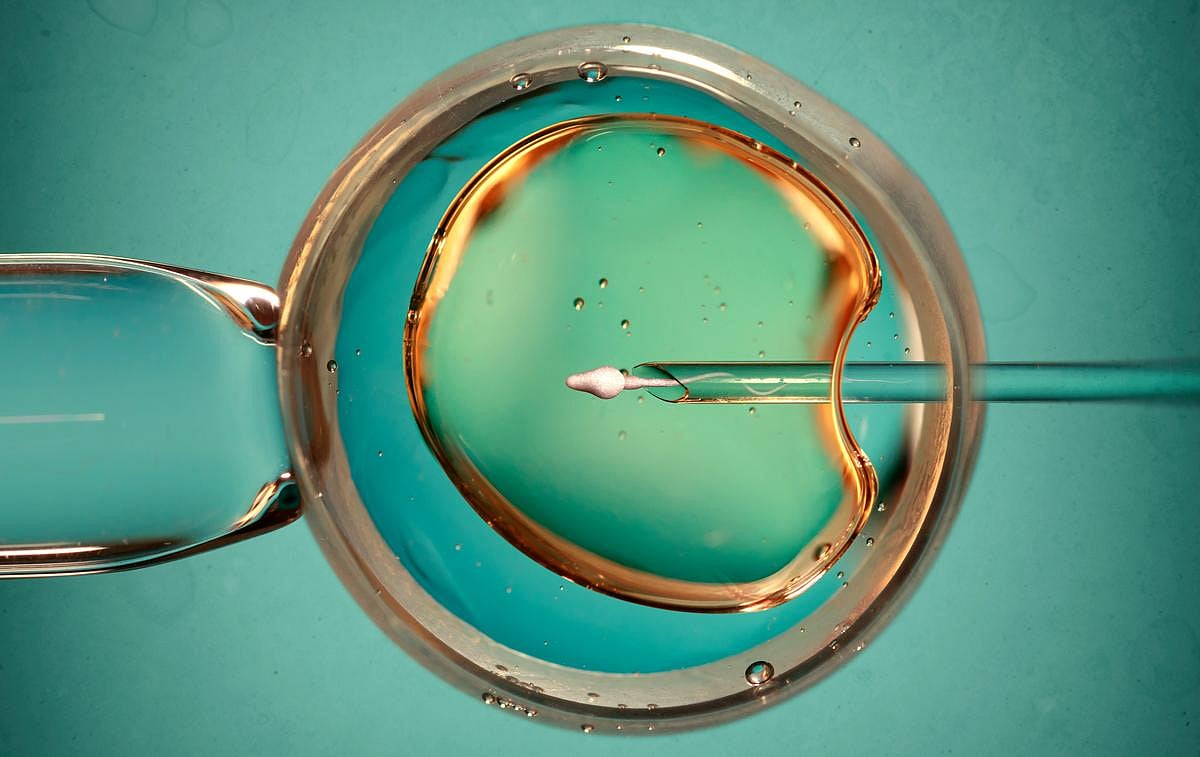

Fertility Treatments Aren't Linked To Added Cancer Risk For Women, Study Concludes

Fertility treatments don’t make women more likely to develop cancer, a new study has concluded.

Women undergoing medically assisted reproduction have no higher overall risk of invasive cancer than other women, researchers reported this week in JAMA Network Open.

However, there are some differences based on specific can...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 13, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Ultra-Processed Foods Bad For Bone Health, Researchers Say

“That stuff will make your teeth rot.”

For decades, parents have tried to steer kids away from junk food with that simple warning.

It turns out such food is bad for your bones as well, a new study says.

People who eat more ultra-processed foods tend to have lower bone density and a higher risk of hip fractures, rese...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 13, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Younger Stroke Survivors Face Unique Mental Health Hurdles

While a stroke is often seen as a condition affecting the elderly, new research shows younger survivors are navigating a silent crisis of mental health and cognitive struggle.

University of Florida researchers warn that while stroke rates are rising among adults under 50, the health care system is failing to provide the specialized support...

- Deanna Neff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 13, 2026

- |

- Full Page

AI-Generated Meal Plans For Dieting Teens Could Be Harmful, Study Warns

Many teens are turning to artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots to help them lose weight by crafting meal plans for dieting.

But a new study warns that those plans are more likely to lead to malnutrition and eating disorders rather than healthy weight loss.

Researchers found that AI-generated meal plans tend to underestimate the nece...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 13, 2026

- |

- Full Page

There's One Simple Way Cancer Patients Can Ward Off 'Chemo Brain,' Study Finds

Cancer patients often speak of “chemo brain” – the brain fog that occurs in some while undergoing chemotherapy.

A new study suggests that exercise might help thwart chemo brain, helping people with cancer stay mentally sharp and better able to handle daily tasks.

Patients following a specially crafted exercise plan ...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 13, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Experts Weigh in on Digital Health Wearables for Neurological Health

The fitness tracker on your wrist or the smart ring on your finger can do more than just count your steps.

These fast-evolving gadgets are becoming valuable tools for managing complex brain and nerve disorders, according to new guidance from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN).

For years, neurologists relied on what patient...

- Deanna Neff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 13, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Pediatric Allergy Specialist: Feed Babies Allergenic Foods Earlier, Not Later

In January 2026, the U.S. Department of Agriculture released new Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025-2030.

Its main message is to promote diets that include whole foods high in protein and full-fat dairy while minimizing ultra-processed foods. As a pediatric allergist/immunologist, I am pleased to see the inclusion of food a...

- Dr. David Stukus HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 12, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Doctors Warn Patients To Research Cosmetic Surgery Providers Before Getting Work Done

A group representing thousands of U.S. plastic surgeons is urging patients to carefully research cosmetic procedures after an investigation raised safety concerns about some surgery chains.

The warning follows a joint investigation by KFF Health News and NBC News that looked into allegations of serious injuries and deaths...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 12, 2026

- |

- Full Page

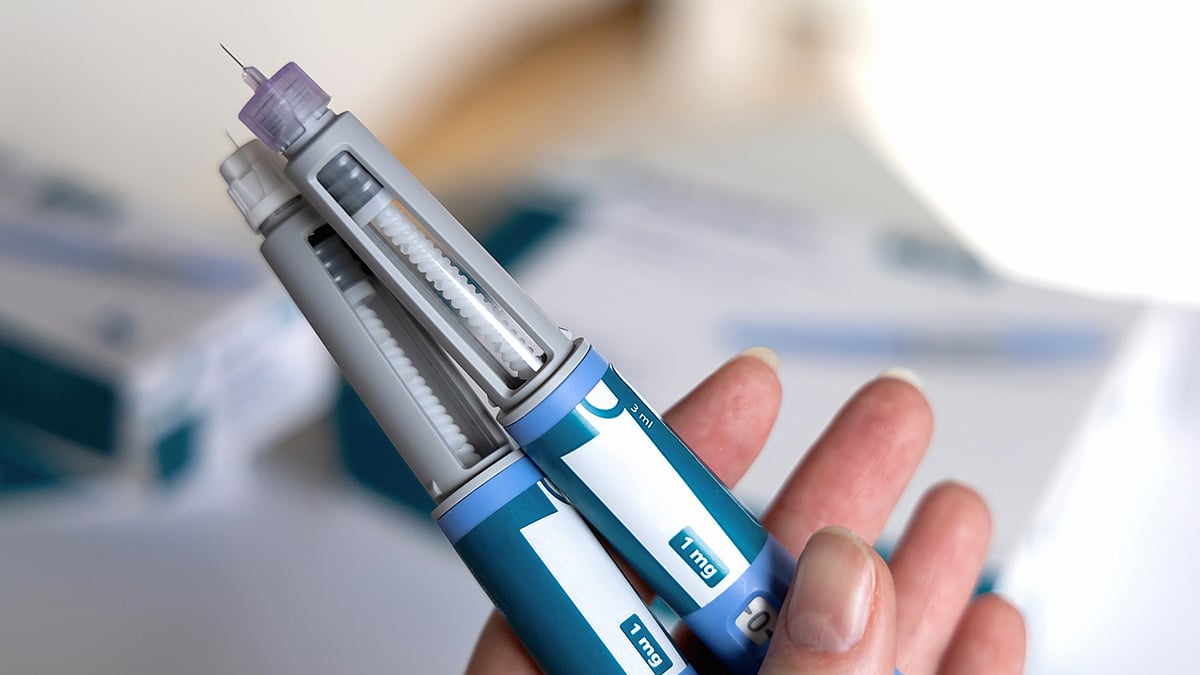

FDA Warns Novo Nordisk Broke Safety Reporting Rules

Federal regulators have warned the maker of Ozempic and Wegovy that it failed to report possible drug side effects to the government.

In a March 5 warning letter, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said Novo Nordisk committed “serious violations” related to safety reporting for semaglutide, the active ingredient in bot...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 12, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Study Suggests Epilepsy Drug May Help Treat Sleep Apnea

A drug used in Europe to treat epilepsy may help people with obstructive sleep apnea breathe more easily during sleep, according to a new clinical trial.

Researchers found that the medication sulthiame reduced breathing interruptions and improved oxygen levels overnight in people with moderate to severe sleep apnea.

The findings were...

- HealthDay Staff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 12, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Millions Of Americans Making Financial Sacrifices To Afford Health Care, Survey Finds

Borrowing money. Skipping meals. Driving less. Cutting back on utilities. Taking meds less frequently than prescribed.

One-third of Americans — an estimated 82 million people — have to make these sorts of financial sacrifices on a daily basis so they can pay their health care bills, a new survey found.

Uninsured people an...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 12, 2026

- |

- Full Page

More Concussions Linked To Worse Brain Health Among Recent College Grads

Former college athletes can show signs of concussion-related brain decline as early as five years after graduation, a new study says.

Athletes who had three or more concussions during college play had worse scores on tests measuring anxiety, depression, distress and sleep quality compared to those without concussions, researchers reported ...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 12, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Switching GLP-1 Medications Is Common, Can Help People Stick With Weight-Loss Treatment

People frequently switch between different weight-loss drugs, swapping Ozempic for Zepbound and vice versa within the first year of treatment, a new study reports.

What’s more, those patients who do swap GLP-1 drugs are more likely to stick with the drugs, researchers reported March 10 in JAMA Network Open.

“Swit...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 12, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Electrodes Partially Restore Movement, Sensation In Spinal Cord Patients

People lose two main things in a spinal cord injury: The ability to control the movement of their limbs, as well as the ability to receive sensory feedback from them.

This two-way communication is crucial for a person to be able to move their legs or arms properly.

Now, a team of researchers reports in the journal Nature Biomedic...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 12, 2026

- |

- Full Page

Years of Specialized Support Essential with Rare Heart Defects

For children born with a single-ventricle heart — a rare defect in which the heart has only one functional pumping chamber — the first few years of life are often defined by a series of high-stakes surgeries.

However, a landmark 16-year study reveals that these operations are only the beginning of a lifelong medical journey.

- Deanna Neff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 12, 2026

- |

- Full Page

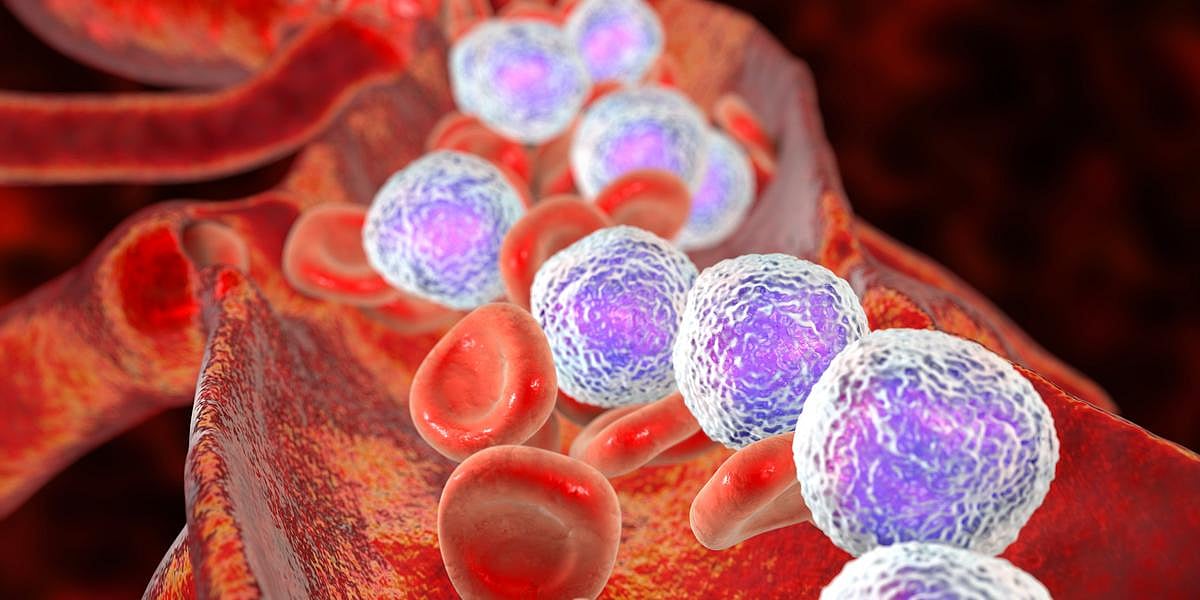

Genetic Test May Predict Leukemia Relapse Risk

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is among the most aggressive forms of blood cancer, and while modern medicine can often push it into remission, the threat of a relapse remains a constant fear for patients.

Now, a step forward in genetic testing could help doctors look deeper than ever before to predict a patient's future health.

In a se...

- Deanna Neff HealthDay Reporter

- |

- March 12, 2026

- |

- Full Page